The Institute publishes new briefing on the Strikes (Minimum Services Levels) Act

Written by Professor Keith Ewing and Lord John Hendy KC

Professor Keith Ewing and Lord John Hendy KC, President and Chair of the Institute of Employment Rights (IER) respectively, have written a up-to-date briefing in the week before the TUC’s Special Conference on the anti-strikes legislation takes place, on Saturday 9th December. In it, the authors say:

“The Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act 2023 became law in July, following a lengthy fight in the House of Lords. It continues the raft of anti-union legislation started by Mrs Thatcher in 1980, making UK law on trade unions ‘the most restrictive in the western world’ as Tony Blair famously described it in 1997. Labour governments did not reverse this regime when they had the chance between 1997 and 2010 and since then, of course, there have been yet further restrictions, including the Trade Union Act 2016.

In consequence, it is extremely difficult for trade unions to do their job of defending working class living standards so that the proportion of our 34 million workers who have the benefit of a negotiated collective agreement has slid from more than eight out of ten in the 1970s to just over two out of ten today. The rest of the workforce are on terms set exclusively by the employer on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. The result has been a marked decline in living standards, half the population earning less than £29,600 pa, far less than the £50,000 a year minimum calculated by the Rowntree Foundation for a family of four to be warm, dry, clean and fed.

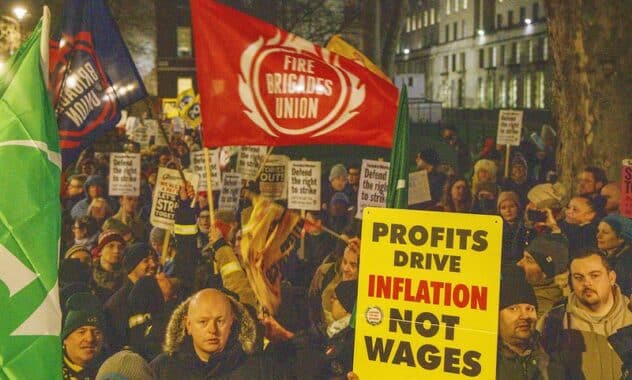

The Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act is not about preventing disruption to the public in a strike. It is about preventing workers through their unions pushing back, as they have been over the last year, against low wages and poor conditions.

The Act is objectionable not just in its underlying purpose but also in its form and content. The form of the Act is significant. It defies every legislative principle laid down by the relevant parliamentary committees which examined the Bill before it was passed by Parliament: Acts are supposed to set out the essentials of what they regulate and only leave technical details to ministers to specify in secondary legislation. Yet the Act fails either to set out the minimum service level (MSL) intended for each of the six sectors to which it applies, or even to specify the factors used to determine them. If the MSLs had been specified in the Bill they would have been subject to debate as the Bill passed through Parliament. Instead, the Act gives the minister complete discretion to set MSLs by regulations – which cannot be amended under our parliamentary system. In December, nearly six months later, the MSL regulations for rail transport, border services and ambulances are going to be published.

The suspicion is that the reason why the MSLs were not specified in the Act is that the government wished to conceal the fact that it intended to use this legislation not just to weaken strikes by certain workers but to remove their right to strike altogether. Had that been disclosed in the Bill, opposition would have been galvanised, particularly in the House of Lords.

The six sectors covered by the Act are: health, fire and rescue, education, transport, nuclear decommissioning, and border security. Millions work in these sectors, including many of the applauded workers who kept the country running during the pandemic. The sectors involve most major unions. But in making regulations, though the Act requires ministers to consult whoever they believe to be appropriate, it does not require negotiation (or even consultation) with the unions – or even employers – directly affected by the Act.

The fact that the MSLs were unknown until this month is one reason why the government’s Impact Assessment of the Bill was held by Parliament’s Regulatory Policy Committee to be ‘not fit for purpose’. Nevertheless, that Impact Assessment contained the revealing analysis that, far from diminishing the disruption strikes inevitably cause, the Bill could lead to: ‘a general increase in tension between unions and employers. This may result in moreadverse impacts in the long term, such as an increased frequency of strikes for each dispute’.

Indeed, since in the current strikes the unions typically will have negotiated local minimum service levels with the employers (as they always do in many of the sectors involved), the imposition of national levels set by government is likely to upset the delicate negotiated balance and intensify the dispute. This is why so many employers, like all the unions, told the government the Act was neither wanted nor helpful.”

To read the full briefing, download it here.