Via UK Parliament’s Transport Committee

A new Transport Committee report outlines key principles for what the Government should include in ‘minimum service levels’ regulations for railway worker strikes.

While the Government’s Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act became law earlier this year, the legislation’s purpose was to empower ministers to make new regulations that would set a required minimum level of service during strikes. Details of those regulations and how they could work in practice have yet to be unveiled by the Department for Transport (DfT).

Following its inquiry, the cross-party Committee has challenged the Government to ensure that regulations it brings forward meet the following criteria:

a) A minimum service level provided on strike days should be at least as good as typically provided on previous strike days;

b) Safety on the network for staff and the travelling public must be the primary consideration;

c) The minimum service level must be flexible enough to be applied to different patterns of industrial action affecting different employers;

d) Regulations should reflect the differential impacts on staff operating rail services on strike days. The greater responsibilities placed on those who must work on strike days to provide a minimum service must be reflected in pay and conditions. Resilience in staffing must be improved so that there are trained alternatives able to cover for specialised staff who may want to exercise their right to strike;

e) The minimum service level must be specified in a way which enables knowledge about travel patterns in particular regions and localities, including access to employment, education and essential services, to be taken into account;

f) Rail services—or credible alternatives—should be available to passengers in all areas of the country normally served by the network;

g) Passengers with access needs must receive the same support as they are entitled to on regular travel days;

h) A minimum service level for rail should protect industries, such as the night-time economy, that cannot adopt flexible and remote working patterns on strike days;

i) There must be clarity about the access that freight services can expect to have to the network, and Government and the freight industry must collaborate on determining what routes should be prioritised.

The Committee also recommends that the following criteria should be used by DfT to assess the success or otherwise of minimum service levels regulations after they have been implemented:

a) Industrial disputes have neither been prolonged nor increased. Novel industrial action has not proliferated;

b) Passenger satisfaction on strike days is greater than at present. Passengers have access to clearly communicated information in relation to service operation, and greater certainty, further in advance than at present, about travel on strike days.

c) Long term, there is more effective cooperation and better working relationships between rail unions, the industry and government.

Chair’s comment

Transport Committee Chair, Iain Stewart MP, said:

“This Committee questioned an array of witnesses from the rail sector and we consistently heard that they were waiting for clarity from the Government on how minimum service levels might be set, how routes should be prioritised, how safety could be guaranteed and which types of staff might be needed. It became apparent that the Government needs to make the first move. Only then will stakeholders be able to feed back on the practicalities, so that regulations can be fine-tuned and plans drawn up.

We therefore say to DfT, once it has determined which model of minimum service level it plans to implement, that it must consult properly with the industry and carefully build on the response it receives.

Meanwhile, in the absence of plans for us to scrutinise, the Committee has put forward nine tests for the Government that should give any future regulations a realistic chance of working for passengers, rail staff and companies, as well as the wider economy which suffers whenever strikes are called.

Among the most vital of those nine tests are around safety and accessibility. We can’t accept an increased risk of lives being put in danger due to a lack of key staff such as signallers, or of those with access needs being neglected if they experience difficulty.”

The options available to government

The report explains that the Government has set out two main options for how to set a minimum service level. Option 1 would see all timetables set at a reduced level of what usually takes place on a normal working day. By contrast, Option 2 would entail a set of routes to be prioritised and stations to remain open. In its consultation Impact Assessment, DfT said that Option 2 was its “preferred option”.

Option 2 has two more considerations: 2a where frequency of services is prioritised on chosen routes with a smaller geographical spread of stations kept open, or 2b where emphasis is placed on running routes over a wider geographical area at the expense of frequency of services.

What currently happens on strike days

Rail Minister Huw Merriman said as an example that during RMT Network Rail strikes in January, about 20% of the network was able to run. However, there was significant variation between train companies. A further case study of an ASLEF strike in February which resulted in a national average of around 40% of services running, illustrating the impact of different workers going on strike.

Unintended consequences

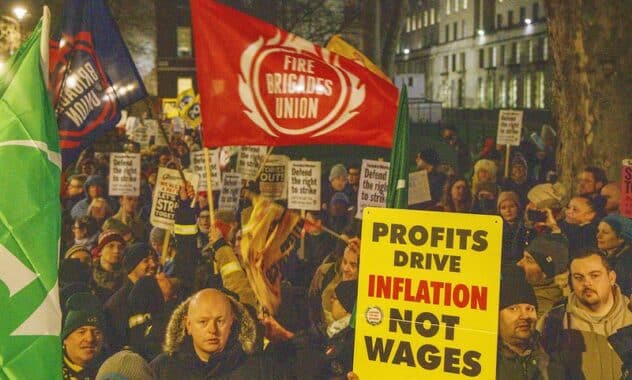

During the inquiry, trade union representatives and others stressed the possibility of new regulations having unintended consequences. It was suggested that poor communication could lead to higher than expected public demand for too few services under a minimum service level; union members who are required to work resorting to novel forms of protest; or service levels becoming less reliable than at present during strike days.

Elsewhere in the report are summaries of the evidence the Committee received on how minimum service levels are operated in other countries, the impacts that strikes and new regulations could have on the rail freight industry, and the reactions that various witnesses had to the principle of minimum service levels.

Aslef general secretary Mick Whelan said:

“Whilst the indenture of British workers is morally wrong, we welcome some interest on what is currently unsafe and unworkable. There is no way, organisationally, that we can comply with the steps in the BEIS and DfT consultation papers but, of course, that is the purpose – to take away the voice of British workers.”