Employment law update November 2023 (London)

Our highly popular annual update on statute, case law and employment rights

Event blog

by Henry Fowler, Head of Research, Campaigns and Organising, General Federation of Trade Unions

The Institute’s ever-popular employment-law update took place at Unite the Union’s London HQ on 22 November 2023 against a backdrop of growing authoritarian legislation targeting the right to strike and protest and the trade-union movement – and the day after the Supreme Court’s perverse judgement that Deliveroo workers cannot be considered employees.

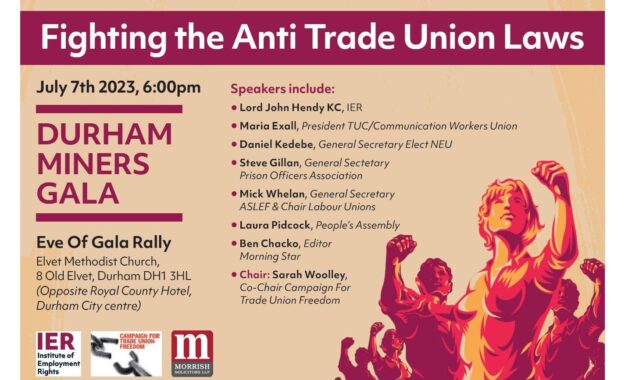

Welcoming delegates, chair Adrian Weir of the Campaign for Trade Union Freedom highlighted the recent TUC/Nautilus/RMT complaint to the International Labour Organisation over the UK government’s failure to sanction P&O Ferries over its cynical and unlawful sacking of 800 UK seafarers.

That failure showed the government’s contempt for rights at home and abroad, and the alarming trend towards increasingly authoritarian laws, including the latest threat to the right to strike posed by the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act, that essentially conscripted workers and their unions to break their own strikes.

Adrian reminded attendees – mostly trade-union reps – that the ILO had debunked the government’s claim that the MSL Act brought the UK into line with other European partners – a theme expanded on later by Professor Alan Bogg – and that both the Scottish and Welsh governments had indicated that they would not use its provisions.

He also stressed that the Labour Party must be held to its commitment to repeal both the MSL Act and the draconian Trade Union Act 2016 that imposed tighter restrictions of strike ballots and mandates.

Roger Ellis of Thompsons Solicitors reviewed developments on holiday pay, including the recent Agnew decision that closed a loophole that had allowed employers to withhold back-pay owed on workers’ right to receive their average pay – rather than basic – when on leave.

Roger pointed out that the Resolution Foundation had calculated that 900,000 workers were still not receiving the holiday pay they were entitled to, and that by the government’s own estimate some 63,000 workers did not receive the national minimum wage.

He reminded delegates of workers’ right to receive four weeks’ holiday pay – enshrined in Regulation 13 of the Working Time Regulations (WTR) – and 1.6 weeks’ bank-holiday entitlement.

However, it was the frequent mis-calculation of holiday pay that was at the heart of many claims for unlawful deduction of wages.

Holiday pay was clearly defined in s221 of the Employment Rights Act (ERA) 1996 and was relatively easy to calculate on a fixed-hours contract, but become more challenging when shift-lengths and hours fluctuated.

Roger detailed the importance of case law and the potential for workers to be dis-incentivised to take holiday, as they could face a financial detriment, based on how holiday pay was calculated.

He highlighted that there were two routes to seeking redress when full holiday pay has been withheld or underpaid: under Regulation 30 the Working Time Regulations 1998, or for unlawful deduction of wages under Section 23 of the Employment Rights Act 1996.

Roger detailed the complications arising from case law for workers making claims for unlawful deduction of wages, especially on the time limits affecting claims, and explored the importance of the Agnew case as a breakthrough for holiday-pay claims.

That claim centred around 3,000 police officers in Northern Ireland, where the recent Supreme Court judgment – which would apply in England as well – meant that claims for holiday back-pay may be made even if there is three-month gap between underpayments, or if a chain of underpayments is broken by a lawful payment, as long as the claim is brought within three months of the most recent underpayment.

The judgment effectively overturned the 2014 Bear Scotland v Fulton Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) judgement.

Roger added that Agnew was helpful as a case as its principles could also apply to other wages claims that revolved around a series of deductions of payments.

Priya Sahni-Nicholas, Co-Executive Director of the Equality Trust, explored the impact of enacting the socio-economic duty (SED) as originally outlined in s1 of the Equality Act 2010 (EA) – which, although shelved by the coalition government in 2010, remained a useful bargaining tool with willing public bodies and employers.

Priya reminded attendees how the EA had combined the content of 116 separate bits of legislation and how s1 was aimed at placing a duty on public bodies to consider the consequences of strategic decisions for levels of inequality and economic disadvantage.

The SED was not to be confused with the public-sector equality duty, which requires public bodies to consider the effect of all decisions on those with the protected characteristics defined elsewhere in the EA.

Priya recalled that the removal of s1 had enabled the government to deliver austerity that would have been illegal under the original draft, but that some local councils had nonetheless voluntarily adopted the duty.

Removing the SED from the Act had resulted in growing inequality, with the UK now reckoned to be the second most unequal country in Europe, and the sixth most unequal among the 38 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Priya presented stark statistics that showed the lowest 10% of earners having to survive on £748 a month after tax while the top 1% enjoyed ‘take home’ pay of £15,000 a month, and that the average pay for FTSE-listed chief executives was 109 times that of an average worker.

Such inequality had deep consequences, including lower life expectancy, lower education attainment and higher infant mortality.

Priya showed that inequality had also grown globally, with the doubling of wealth held by the world’s top 0.1% between 1984 and 2013 and a 9% increase in billionaires: a “funnelling up” of money that had left many millions in poverty.

Priya noted that this was not a modern phenomenon, and that policy decisions in the UK were often centuries in the making – policies made by the rich and powerful to perpetuate their wealth and control.

However, adoption of the SED offered a counterbalance, an ‘oven-ready’ solution to this overwhelming inequality and its detrimental effects on society, and that areas that had implemented it had begun to see real benefits.

The SED had been adopted in Newcastle in 2012, Scotland in 2018 and Wales in 2021.

In Scotland the aim was eradicating poverty altogether, including ending the need for food banks, a less-pronounced difference between rich and poor and ending child poverty, and it was thanks to the SED that child poverty in Scotland was 5% lower than the rest of the UK between 2019 and 2022.

Priya noted that reducing inequality had high support among the public, with 78% agreeing that government should consider the impact of its policies on people who were less well off, and that the Labour Party was committed to enacting the SED as part of its five mission pledges intended to be at the core of its next election manifesto.

The Equality Trust was now working closely with local authorities and bodies around the country, said Priya, noting that each had developed its own local strategies, involving building relationships in communities and among activists and other public bodies, empowering people to create sustainable strategies for delivering change.

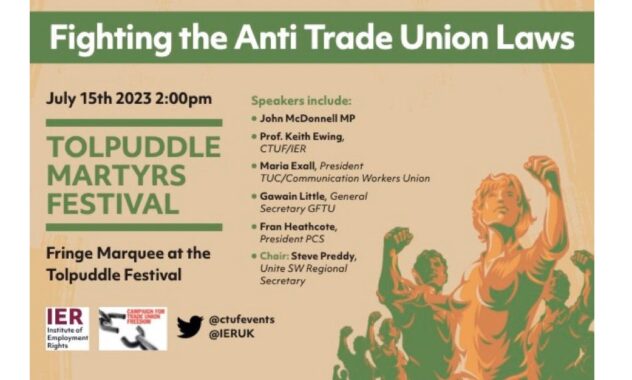

Alan Bogg, Professor of Law at Bristol University and barrister at Old Square Chambers, detailed how the government’s use of a “false alibi” of comparative laws in Europe as a justification its Strikes (Minimum Services Levels) Act was fundamentally flawed.

He noted that Grant Shapps MP had argued that the Act resulted from a need to bring UK labour law into line with other European countries, but that this had relied on misleading ‘cherry picking’ from other countries’ legal frameworks and failing to understand those frameworks as a whole and the status of the right to strike in comparator countries.

Alan underlined how the UK already had amongst the most restrictive labour laws in Europe, maybe the world, and that its violations of ILO regulations were matched among European nations only by Turkey and Russia.

A genuine comparison should involve key metrics including the legitimacy of strike action, including political and secondary strikes, constraints on strike ballots and protection of individuals’ right to strike.

While the UK didn’t allow secondary or ‘political’ strikes, in Spain, France, and Italy, with specific conditions in each countries’ own law being met, secondary strikes were legal.

Alan pointed out that secondary action became important when employers like P&O fired staff to replace them with cheaper labour, but workers in the UK connected with the ports and other services alongside P&O ferries were unable legally to support their fellow workers, and with no government sanction the employer got away with it.

Balloting rules also see the UK out of step with Spain, France, and Italy. In both Spain and France the right to strike is a constitutional right of individual citizens, and therefore the need to ballot unconstitutional. In Italy the right to strike is also that of the individual.

Spain, France, and Italy also share a suspension of employment contract during strike action and various degrees of protection against dismissal, again unlike the UK, where there is only limited protection, and striking workers are in breach of their contracts.

Alan concluded that serious reform in the UK would need to see contracts of employment suspended during a lawful strike, with strikers protected from victimisation associated with participating in a lawful strike; secondary and political strikes legalised in line with the comparative examples elsewhere in Europe, combined with e-balloting allowed for all action, and the abolition of the restriction imposed by the TUA.

Paul Scholey from event sponsors Morrish solicitors presented an update on developments in discrimination law.

Paul revisited the Forstater v CGD Europe case, noting that the claimant had been awarded £105,000 by the Employment Tribunal in aggravated damages and loss of earnings and potential earnings after a successful appeal which had established that gender-critical beliefs were protected under S10 of the Equality Act, while a further case, Fahmy v Arts Council England, had underlined that “Forstater is here to stay.”

Paul also discussed the 2023 increase in ‘Vento bands’ that inform awards for injury to feelings in discrimination and whistleblowing cases, with the lower band ranging from a minimum of £1,100 to £11,200, the middle band ranging up to £33,700, and the upper band up to £56,200, with the most exceptional cases exceeding that figure. He noted that Forstater had been placed at the upper end of the middle band.

Paul noted that an earlier case had established that ethical veganism was a philosophical belief protected under the EA, but in Owen v Willow Tower Opco 1 Ltd the claimant, a care worker who had been dismissed after refusing a Covid vaccination, had failed to provide enough evidence that her veganism was indeed a philosophical belief, rather than a “viewpoint” that was not protected.

Highlighting new research on intersectionality from the McKinsey Institute for Black Economic Mobility, Paul described how it had found that while 66% of UK employers had high female representation and 50% had high representation of people from ethnic minorities, only 17% had high representation of people with both characteristics.

Turning to harassment, Paul touched on the importance of perception in the case of Greasley Adams v Royal Mail Group, in which a claim had been brought by a manager who had learned of comments made about him by colleagues during a bullying and harassment investigation against him. The Tribunal found that his counter-claim was not founded as he had been unaware of the comments and could not therefore have perceived that he was being harassed.

Paul also discussed the Protection from Sex-Based Harassment in Public Act 2023, which amends the Public Order Act 1986 to create a new criminal offence of intentional harassment, alarm, or distress on account of sex. Passed as a short ‘skeleton act’ – and thereby avoiding much parliamentary scrutiny – the detail would be published as a Statutory Instrument.

Additionally, the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Act 2023, creates a new duty for employers to take “reasonable steps” protect employees from sexual harassment, although during its passage the House of Lords diluted the originally drafted requirement to take “all reasonable steps”, and removed a requirement to protect employees from third-party discrimination. The Act comes into force in 2024.

Paul described a new British Standards Institution workplace standard on menopause and associated issues. While menopause itself could not be seen as a disability under the EA, the associated physical and mental conditions could constitute a disability.

In McCabe v Selazar Ltd (ET) 2021, the then 55-year-old claimant, who had been told to “calm down, don’t let your hormones get out of control,” won her tribunal on the grounds of age discrimination and unfair dismissal, rather than discrimination on the grounds of menopause.

Paul recalled Marchant v BT plc (ET) 2012, in which the claimant, who had provided a GP letter saying that her menopause-linked symptoms could affect her concentration, was dismissed for poor performance. The employer admitted that the case would normally have been referred to occupational health, rather than rushing to dismissal, and in this case the ET decided that it was sex discrimination.

Paul also reviewed cases which explored the defence against discrimination claims arising from ‘genuine occupational requirements’ and the law around disability, sickness and disciplinary measures.

Keith Ewing, Professor of Law at King’s College London and President of IER, focussed on developments around Labour’s New Deal for Working People, which had originally envisaged the creation of a Ministry of Labour to oversee the introduction of sectoral bargaining and the restoration of workers’ rights.

Labour’s plans risked being reduced to piecemeal change, rather than the fundamental transformation needed to make lasting change on employment rights, including the abolition of zero-hours contracts and outlawing of ‘fire and rehire’ practices.

Outlining how much needed to be done, Keith contrasted the European Union’s stated aim for member states to have at least 80% of workers covered by collective agreements with the current level of 20% in the UK – lower than in any European country other than Lithuania.

He detailed what a future Labour government could do, including changing the law to empower workers and ensure that employers knew that if they breached the rules, as with P&O, there would be consequences.

P&O’s ability simply to pay compensation for breaching labour standards highlighted the need for change: there was currently no UK law stopping an employer terminating collective agreements with recognised trade unions and undertaking actions detrimental to workers.

Without the ability to take solidarity action, there would be more examples like P&O, and so reform to labour law under a Labour government must include the reinstatement of that right.

The day’s final session brought together a panel linking the increase in authoritarian law limiting the right to boycott, protest and strike.

Adrian Weir of the Campaign for Trade Union Freedom outlined the coercive nature of the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act and its implications for trade unions and their members, including financial penalties up to sequestration and dismissal of strikers without recourse to tribunals.

The legislation was aimed at six sectors – the health service, fire and rescue, education, passenger transport, nuclear decommissioning and border security.

It gave the right to employers to issue work notices to unions identifying individual workers required to work during a strike. Workers refusing to comply could be dismissed without protection for unfair dismissal, and unions failing to take “reasonable steps” to ensure that its members complied would be liable for damages and sequestration of assets.

There were currently three draft statutory codes of practice – for ambulance paramedics, border security and rail workers (with separate codes for passenger, infrastructure, light rail).

Those codes required unions to identify their members from the list in the work notice; contact and encourage individual members to comply with the work notice, and ensure that picket supervisors to took reasonable steps avoid trying to persuade members identified not to not cross a picket line.

Jackie Simpkins, War on Want’s Trade Union Officer, detailed the effect that the “boycott bill” – the Economic Activity of Public Bodies (Overseas Matters) Bill – would have on the democratic right to protest.

Cited by government to stop divestment and boycott campaigns against Israel, it would in practice limit the ability of local authorities and universities to make ethical decisions around suppliers and service-procurement.

Jackie pointed out the hypocrisy involved when the government itself had written to public bodies last year urging them to go beyond government sanctions and cut ties with all companies run by Russia and Belarus.

She pointed out that the Scottish and Welsh parliaments had indicated that they would withhold legislative consent.

Jun Pang, Liberty’s Policy and Campaigns Officer, described the attacks on the right to protest through the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 and the Public Order Act 2023, severely limiting the right to protest and effectively criminalising gypsy and travellers’ communities with new criminal-justice powers.

Jun noted that resistance to the measures had seen civil society, unions, and gypsy and traveller communities working together, a coalition which would continue to be important in the future.

The Public Order Act included draconian measures around the noise made by a protest, and stronger restrictions on static protests, including direct limitations on protests around Parliament, with the secretary of state given greater powers to clarify what constitutes serious disruption to the life of the community.

It also gave police the right to police to stop and search with or without suspicion and deliver “Serious Disruption Prevention” orders. New criminal offences included locking on or going equipped to lock on; interference with key national infrastructure, and causing serious disruption by tunnelling.

Jun noted that the Public Order Act 1986 (Serious Disruption to the Life of the Community) Regulations 2023, gave police powers to impose conditions on protests.

While it was important to understand the risks when organising protests and other collective actions, it was also vital not to allow them to stop our right to protest.

Download event documents

- Holiday-Pay.pdf - 230.20 KB

- SED-Priya-Sahni-Nicholas.pdf - 1.13 MB

- Alan-Bogg-IER-Presentation-RTS.pdf - 71.70 KB

- Paul-Scholey-presentation-Discrimination-Law-IER-11.23-fin.pdf - 617.79 KB

- PandO-Ewing.pdf - 52.37 KB

- WoW-IER-BDS-talk-Nov-2023-JS.pdf - 89.07 KB

- PCSC-and-POA-IER-slides-Liberty.pdf - 1.14 MB