Government’s controversial Public Order Bill met with opposition

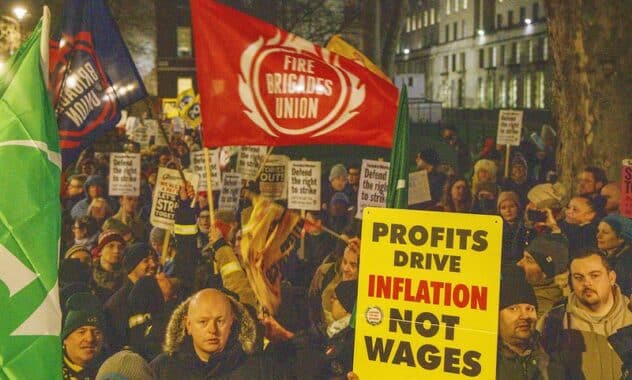

Union concern that measures will be used against pickets in industrial disputes.

This afternoon, the Government’s Public Order Bill has its second reading in the House of Commons. The Bill represents Home Secretary Priti Patel’s latest attempt to introduce legislation that has previously been blocked by the House of Lords as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Bill.

In September and October 2021, environmental campaign group ‘Insulate Britain’ held a series of co-ordinated protests. The protests, designed to coincide with the passage of the PCSC Bill through the House, involved group members blocking major roads and protestors gluing themselves to the roads to make it more difficult for police to move them.

In the wake of these protests, the Government sought to expand the Bill to include a range of amendments to give police greater powers to respond to this kind of protest and increase the criminal sanctions available.

However, these amendments were rejected by the House of Lords at report stage. In response, the Government is continuing to pursue the measures by reintroducing them through the Public Order Bill. This Bill would bring in three major changes to the way protests are policed in England and Wales.

- Expanding protest related offences: the Bill would introduce four new criminal offences related to disruptive protest including “locking-on”; being equipped to “lock-on”; obstructing major transport works; and interfering with key national infrastructure.

- Extending police stop and search powers: the Bill would provide the police with new powers to stop and search people for items related to specified protest-related offences.

- Introducing a new preventative court order: the Bill would create Serious Disruption Prevention Orders aimed at people who repeatedly engage in disruptive protest activity. The orders would be issued with conditions to prevent individuals from being in particular places or with particular people or from participating in certain activities.

Police authorities are generally supportive of legislative change to policing protests. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Andy Cooke described the legislation as “a modest reset of the scales” between the rights of protestors and the rights of others.

However, the Government’s approach has been hugely controversial and attracted strong criticism from human rights campaigners who have been critical of the expansion of police powers and increased criminal sanctions.

Two ‘reasoned amendments’, critical of the Bill, have been submitted. The first, a cross-party amendment laid by Streatham MP Bell Riberio-Addy, states:

“That this House declines to give a Second Reading to the Public Order Bill as it includes certain measures which disrupt the much needed balance between freedom of expression and the protection of the public, such as the significant expansion of police powers to restrict protests, the expansion of stop and search powers, and new offences relating to locking on and other forms of protest and civil disobedience.”

The second, tabled by the Labour front bench, reads:

“That this House declines to give a Second Reading to the Public Order Bill because, notwithstanding the importance of safeguarding vital national infrastructure alongside the right to protest peacefully, the Bill does not include provisions for cooperation between police, public and private authorities to prevent serious disruption to essential services, includes instead measures that replicate existing powers, includes powers that are too widely drawn and which erode historic freedoms of peaceful protest, ignores the need for effective use of existing powers and does not recognise emergency NHS services as vital national infrastructure.”

The Government have been keen to make the case that the measures in the Bill apply to a handful of extremists and will not impact peaceful protests or freedom of expression. This has been met with some scepticism by campaigners. Human rights organisations have been critical of the Bill, with Liberty arguing that the measures were an attempt to hide from accountability, whilst criminalising demonstrators.

“Protest isn’t a gift from the State. It’s our right” they said on their Twitter account.

There is significant unease amongst trade unions about the proposed legislation. Many trade unionists will be concerned that these measures will be used against pickets in industrial disputes.

Writing in the House magazine, Bell Ribeiro-Addy said:

“Time and again, protest and activism have given a voice to the voiceless and dragged us into confronting vital issues. But the message from the government couldn’t be clearer: put up and shut up.

This attempt to criminalise dissent is a threat to everyone’s right to stand up for what they believe in and for anyone who believes in building a better society where nobody is left behind. We must defend our right to protest.”

During the debate on the Bill in the Commons, she said that whilst the Bill states that there will be a legitimate defence where the disruption is due to a trade dispute, this defence is not available to prevent the new protest banning orders (‘Serious Disruption Prevention Orders’) against people who have taken part in more than one protest within a five-year period. It is clear that union officials who regularly attend pickets will be particularly vulnerable to this part of the legislation.

Ribeiro-Addy added that with the Trade Union Act 2016, the Police, Crime and sentencing Act this year (allowing police to impose conditions on noisy pickets) and now this Bill, the Government have all but eradicated what was already a severely restricted right.

Lord John Hendy, Chair of the Institute of Employment Rights, said:

“This is another blow is aimed at trade unions, the only organisations capable of fighting back against the relentless and accelerating attack on working class living standards.”