Ben Sellers

Ben Sellers, worked for the TUC between 2007 and 2011, first as a graduate of the Organising Academy and then... Read more »

Financial Times economists’ survey - extracts

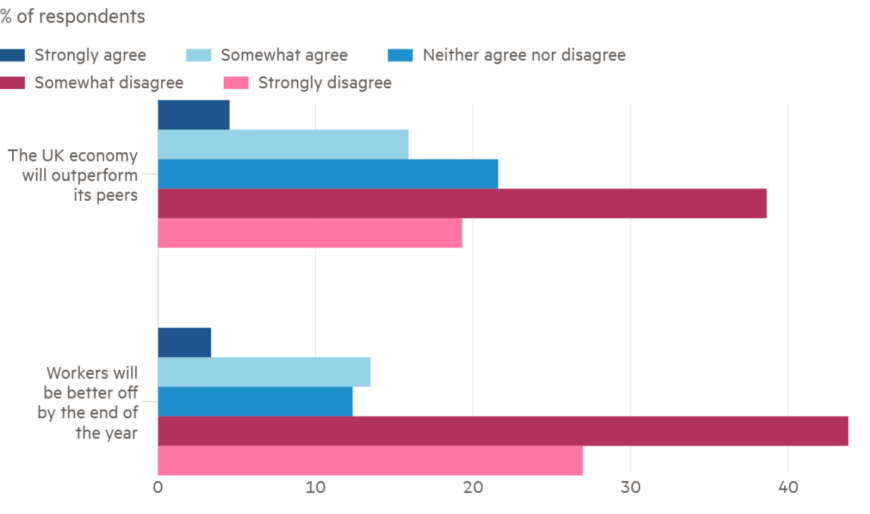

On the 3rd of January, the Financial Times published an extensive survey, asking a range of economic experts for their responses to the current economic situation in the UK and prospects for the year ahead. What came out of it was fascinating, with many areas of agreement about the challenges ahead, both for the economy and workers.

Here is a selection of those responses (continued as a pdf document in the link below):

Diane Coyle, Bennett Professor of Public Policy, University of Cambridge:

“Old problems — low investment, low levels of private R&D, inadequate infrastructure, the dysfunctional housing market, policy instability — and new problems — Brexit headwinds, political uncertainty, loss of skilled migrant labour — mean the UK will lag other comparable economies.”

Dhaval Joshi, chief Strategist, BCA Research:

“The UK economy will lag its peers in 2022. The UK economy fell furthest in the first wave of the pandemic, with GDP collapsing by 22 per cent, compared with 12 per cent in Germany, 10 per cent in the US, and 8 per cent in Japan. So, unsurprisingly, in the subsequent rebound, the UK has bounced the strongest. But now that the post-pandemic rebound is mostly complete, the ongoing headwind from Brexit will become the main differentiator of UK growth versus other developed economies.”

On average, people are likely to feel little progress, if not a squeeze, in real terms pay during much of next year.

Ann Pettifor, director, Policy Research in Macroeconomics (PRIME):

“UK trade performance on imports and exports have been among the worst of all OECD economies, with Brexit exacerbating the pandemic. This significant fall in total trade (compared to 2018) is an outcome, or consequence, of weak economic activity at home. Flat business investment is an ongoing key constraint. That is why we expect the UK will perform (in GDP terms) below the level of advanced economies in 2022. Annual GDP is likely to rise by around 3.5-4 per cent (well below HMT’s ‘comparison of independent forecasts’ which range up to 8.1 per cent). UK GDP fell further in 2020 than almost all other OECD countries and ‘rose’ a bit faster in consequence in 2021, partly due to technical reasons in ONS calculations of public sector ‘production’. We consider this ‘catch-up’ has now ended. Tax rises and ‘new austerity’ measures will constrain economic activity further.”

Jonathan Portes, Professor of Economics and Public Policy at King’s College:

“It’s notable that despite a profusion of media reports about wages rises over the summer, real wages are still lower than a year ago and have been falling, not rising, in recent rates, as inflation has taken off. This won’t reverse immediately, although things may improve as inflation recedes. To be fair to the Government, boosting wages and productivity in a sustainable manner was never going to be either easy or quick.

Unfortunately, the Government seems to be keen on quick, politically attractive fixes. Focusing on a few areas and seeking to create ‘good manufacturing jobs’ — even if it is in the industries of the future, such as renewables — is only going to be at most a small part of the answer for a small number of places. Meanwhile, reducing immigration will in itself do little or nothing to boost pay and productivity and may indeed make things worse.

Indeed, a liberal and flexible migration policy — for a small open economy like the UK, highly dependent on high-productivity service sectors — is likely to be an essential ingredient in any credible strategy to boost productivity.

A high wage high productivity economy will require both national and local policies addressed at both people and places, and that don’t pit poor people in London and the cities against deprived areas in the north and Midlands. This means investment in connectivity — physical and digital — that allows skilled workers to have productive, well-paid jobs wherever they live; investment in people, that narrows the divide in skills and productivity between those who go to university and those who don’t; and a new model of the labour market and welfare system that instead of forcing people to take any job — no matter how insecure or precarious — shares risks between employers, workers and the state so as to expand choice and opportunity.”

UK GDP fell further in 2020 than almost all other OECD countries and ‘rose’ a bit faster in consequence in 2021, partly due to technical reasons in ONS calculations of public sector ‘production’. We consider this ‘catch-up’ has now ended. Tax rises and ‘new austerity’ measures will constrain economic activity further.

Alfie Stirling, Director of Research and Chief Economist at the New Economics Foundation:

“A year is too soon to make much progress on underlying productivity, and much too soon to be able to reliably measure it. Much of the data on productivity will continue to be clouded by statistical artefact and noise for some time, due to the knock-on effects of the pandemic.

There will be more clarity around living standards. The recovery in nominal wages is likely to face further headwinds this year — either due to future waves of infection and a lack of economic support, or premature monetary tightening, or both — and this will be eroded still further in real terms by continued high inflation. On average, people are likely to feel little progress, if not a squeeze, in real terms pay during much of next year.

But such averages will also continue to mask continued divergence and inequality in living standards over the next 12 months. Higher inflation will bite hardest for those on lower incomes who spend more and save less, and especially those that spend a higher proportion of their incomes on fuel and energy. Meanwhile, policy changes such as national insurance rises, which take effect in April, will hit earnings from work far harder than income from capital.

NEF modelling has shown that over the past two years — Dec 2019 to Dec 2021 — the poorest half of UK households are £110 per year worse off on average, while the richest 5 per cent are more than £3,300 better off. On the present trajectory, it is unlikely that this pattern will have been reversed in a years’ time, and more likely it will have been made worse.”

Andrew Smith, Economic Adviser, Industry Forum:

“The government is repeating the same mistake as the past decade — targeting the budget deficit when it should be using fiscal policy to support growth. It will have the same results — depressing growth and making it more difficult to cut the deficit. Bonkers.”

For more responses from the FT’s economists’ survey, click here.

Ben Sellers, worked for the TUC between 2007 and 2011, first as a graduate of the Organising Academy and then... Read more »

‘Failing to succeed’: the role of Cambridge economics in making the case for the minimum wage