How the ministry of labour will defeat neoliberalism

The work of the Institute of Employment Rights (IER) over the last three decades has been essential and remains so today.

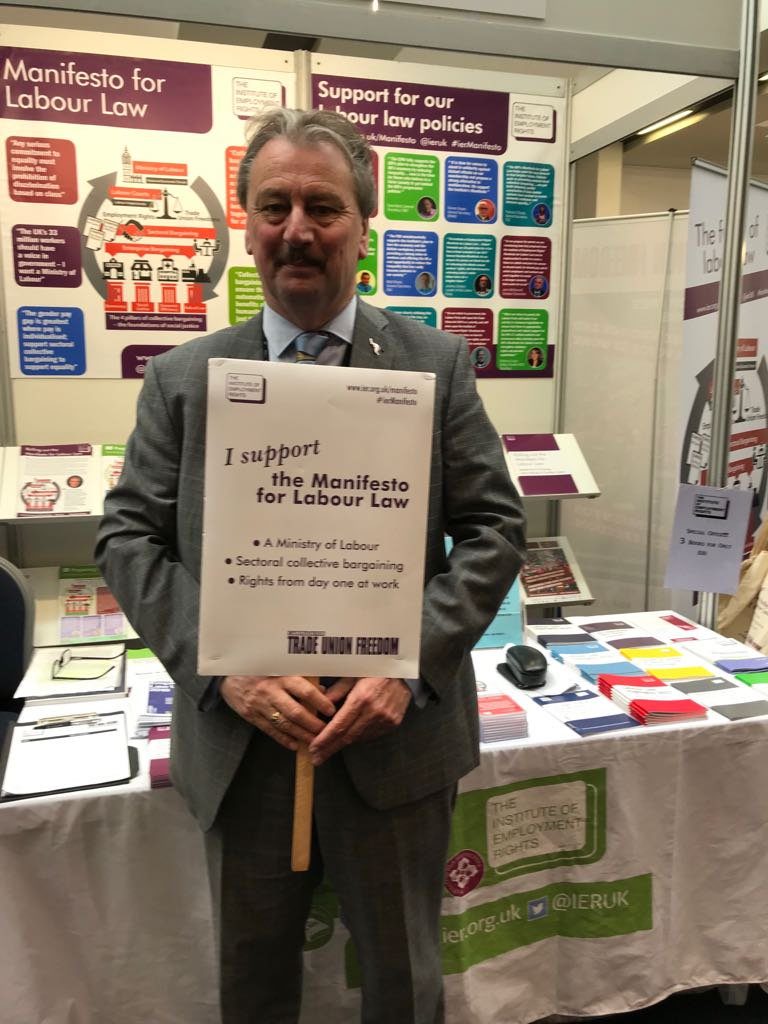

The IER has been advising me in my role as shadow minister for labour, but much more than that, it’s been instrumental in providing the building blocks for a new department in a future Labour government, a ministry of labour, which I believe will be transformative for workers and workplaces.

It’s such an important and exciting part of Labour’s programme and I’m delighted to be heading it up.

So where are we at? Many workplaces are hostile environments, for both workers and their representatives, the trade unions. That isn’t good for us, as a labour movement, the economy or society.

We have a generation of people for whom work means stress and insecurity, where their rights are seen as insignificant in relation to the power of their employers, where contracts are temporary and where their wage doesn’t pay the bills. People in this country are underemployed, overworked and poorly paid.

And the roots of this hostile environment? The answer is obvious. It’s about a lack of union power and the decimation of bargaining coverage, that is for trade unions to be able to negotiate the terms, conditions and rates of pay of workers.

What we must do is explain that to people who’ve grown up in an environment where unions have been stigmatised or ignored. But that is the reality: even the Institute for Financial Studies — hardly a bastion of revolutionary thinking — has recently pointed out the correlation between pay inequality and a rapid dwindling of trade union power and membership.

As the work that John Hendy and Keith Ewing have done via the IER has shown, the percentage of workers covered by a collective agreement has gone from 82% to around 22%.

In the private sector it is even worse — it’s impossible to say precisely, but collective bargaining coverage in the private sector is generally considered to be around 15%.

The roots of this are entirely political: they lie in a neoliberal political project Margaret Thatcher heralded from the 1970s onwards. The deliberate strategy of the Thatcher government was to take on the unions in order to make the British economy work for a different, free-market model — making

a quick profit on the back of low pay and insecure contracting.

Its aim was to individualise and atomise work and shift the cultural norms of the British workplace explicitly to divide workers.

And of course, that had a knock-on effect. It was remarkably effective in lowering worker confidence. While the miners fought on, through a year of the miners’ strike in the mid-1980s, their ultimate defeat was another hammer blow to the idea of collective strength of the unions.

Now, we have two generations who have not experienced collectivism of the kind that could fundamentally shift the hold of employers over workers and a generation who do not know what a trade union is for and the power of workers standing together. It was such a successful strategy.

We now have workers who are scared to ask to go to the toilet, urinating in bottles, miscarrying at work, there are chicken factory workers in the US who have to wear nappies because they are not allowed toilet breaks.

Of course, in between those defeats and the situation we’re in right now, where precarious work has become commonplace, we had three New Labour

governments.

That could have been an opportunity to roll back some of the Thatcher revolution, but instead it was an opportunity wasted. Not only did Tony Blair and co fail to remedy the anti-trade union laws, in some cases they boasted that we had the most restrictive labour environment in Europe.

Of course it is easy to pay lip service to the unions and unionised workers. There are still six million trade union members and even the current government is aware of this fact.

So, while they restrict facility time, enact legislation which makes negotiation harder, strip away rights and force unions to jump through ridiculous bureaucratic hoops to take strike action, they also set up the Taylor review, or to give it its full title: “Good Work: the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices.”

But Taylor fundamentally misses the mark, because it does not acknowledge the structural problem, which is lack of union role in our workplaces.

So, how would we respond, as the Labour Party in government? The first thing to say is that we would acknowledge and build our solutions around that gap: we would put unions and their members at the heart of our economy. Easier said than done of course, which is why we have a plan.

That plan involves creating a ministry of labour, bringing back a department specifically designed for workers, their rights and industrial relations.

This was abolished by Thatcher and unsurprisingly, the current Tories have no interest in bringing it back.

So, even though I am shadow minister for labour, I have no opposite number. Which doesn’t mean that I don’t get to ask questions in the House of Commons, just that they have to scrabble around to find someone to answer them — what a disrespect to workers.

Sectoral collective bargaining will be the beating heart of that department — because the institution of collective bargaining, that is, the ability for workers to negotiate their pay and conditions, collectively, changes everything.

The ministry of labour will also oversee an uplift of the statutory minimums — not just on pay, but things like maternity and paternity pay. We will also take enforcement seriously and create a labour inspectorate to enforce those minimums — because they are useless if they are on paper only.

We’ll also put equalities at the centre of this new working environment. And this will work hand in hand with an ethical social security system headed up by Margaret Greenwood, our shadow work and pensions secretary.

We’re not tinkering any more, because we know that will not be enough. After 10 years of austerity and three decades of free-market dogmatism, we know that only a radical change will shift our society in the direction of workers.

I am so excited and energised by this project and the work that I’m doing with Ewing, Hendy, the IER and trade unionists from all over the country — because, if we work together, and get it right, it will result in the largest transference of power from bosses to workers in generations.

Thank you for all the work you have put in, as trade union reps and organisers and activists over the years. Please see this project as your project — and a future Labour government as us all going into government together.

Of course, there is an obvious onus on the trade union movement, too, and will need to meet that challenge.

There will need to be a concerted effort to recruit. It will be our aim, in government, to provide the legislative framework for trade unions to organise; to have access to the workplace; for workers to have the right to withdraw their labour.

But it will be a joint effort, the political and the industrial halves of the labour movement coming together. That’s the only way we will succeed — and I think we will, comrades.